シベリアの奥地、タイガへの旅

Siberia, the heart of the Great Russian Wilderness, is a place where one can travel through thousands upon thousands of miles of forest broken only by rivers and lakes. The Taiga forests, known to the locals as Taiga-a-a-a, they lengthen the word as if to emphasize the endlessness of the landscape. For Russians who remember the days of the Cold War and the reign of Stalin, Siberia was the stuff of nightmares, of gulags and wretched cold. Siberia was where you were sent to slave labor camps until you were worked to death, and for most, it was a sentence of just a few weeks. Even today the word is whispered, as if saying the name of the place aloud will bring its curse down upon you.

This is where I chose to spend the summer of 2016. Years before someone had told me of breeds of horses that live there in winters of minus 50 degrees or even colder, surviving by entering into a state of semi-hibernation to conserve their energy. Here there were reindeer herders who called the empty wasteland their home. There were also tribes who still worshiped the God of Fire, the God of the Hunt, tribes with names like Nenet, Yakut and Evenki. My plan was to rent or buy one of these legendary horses and ride alone into the Taiga. And despite having already made long solo horseback journeys in Mongolia, Tibet and Afghanistan, the thought of Siberia terrified me. In the other places I had ridden, I had always found people, possibly days apart, but always someone and somewhere, willing to take me in and provide me with food and shelter. In the Taiga there would be no one. However, two simple statistics drew me; its total land area was 3,083,523 square kilometers, almost the size of India, yet its population was a mere 950,000.

I flew into Yakutsk, the capital of the Yakutia, also known as the Republic of Sakha. For a few days I explored the pleasant little city with its mammoth exhibits and diamond museums, before heading north on a non-stop twenty-eight-hour drive to the village of Tomtor in the heart of the Taiga. In contrast to modern Yakutsk, Tomtor was a ramshackle dot on the map with wide mud streets and wonky houses. Here I slept only one exhausted night before taking a truck ride out of town along the Road of Bones, so named because the forced labour that built it were buried beneath their own handiwork when they expired, to where a horse was waiting for me.

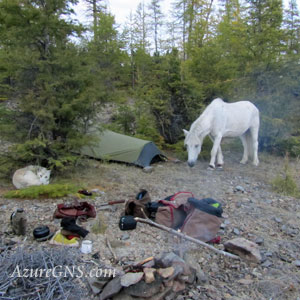

“Katchula!” the man said and pointed to the white horse tethered to a post, “His name is Katchula, it means ‘money’ in Yakut language.” The man, a member of the ethnic Yakut minority who had migrated from regions around Mongolia a thousand years before, had Oriental features and spoke his own dialect. We settled on a price per day to rent Katchula and he lent me a saddle and bridle. I loaded my saddlebags onto the horse and climbed onto the animal’s back.

“Be careful of bears!” the man called after me as I headed back down the road and onto a muddy track that led straight into the Taiga.

Despite the cloudy and sunless sky, I soon realized I had a shadow. A white Yakut dog with a curled-up tail had followed me from the farm where I’d met Katchula. Along the road I’d tried several times to send him back home knowing that I hadn’t bought dog food to support him, but he kept coming. And as we entered the Taiga and the landscape’s vast emptiness had started to hit me, my attempts to send him away became weaker and weaker. That night, my first camp in the Siberian wilderness, I made a fire from dry larch wood and cooked rice in which I mixed in a tin of meat. I shared half my meal with the dog and our little expedition team of three was settled. Later I would find out the dog’s name was ‘Dogor’, a Yakut word meaning ‘Friend’, so now I had Money and a Friend, what else could I need?

Three mornings later that question would be answered in dramatic fashion; a shot gun! After a breakfast of hot tea, I saddled Katchula and started loading the saddlebags onto his back when a commotion broke out in the forest just above my camp. Dogor lit up with a frenzied barking, something was chasing him through the undergrowth growling, grunting and puffing; a bear! The two foes burst from the scrub with Dogor just inches ahead of the magnificent brown bear’s jaws. The bear, suddenly spooked in the open without cover, turned and fled back into the safety of the trees with brave Dogor snapping angrily at his heels.

I stood with shaking knees next to Katchula as he snorted with fear while Dogor and the Taiga’s largest and most feared predator sparred back and forth in the forest. I tried calling Dogor away but he had been trained as a hunting dog and in his mind was just doing his job - he was also probably wondering why no one was rushing to back him up with some serious firepower. After several minutes of combat without a clear winner, the bear seemed to give up and wandered off into the forest, still with Dogor yapping after him. I climbed, on wobbly legs, into the saddle and headed off in the opposite direction.

That day, which had begun with a bear in my camp, ended in the company of new friends, with good food in the safety of a warm log cabin. I reached Lake Lybunkur which stretches from north to south between two mountain ranges about eighty kilometres south of Tomtor village. The cabin, owned by a Yakut semi-hermit called Ruslan, was actually a rustic hunting and fishing lodge. His guests were a couple from Yakutsk, Alex and Sakhayana, who had flown in by helicopter a few days before to go fishing and duck shooting. The lodge was equipped with a wood-fired bathhouse and sauna, solar panels for electricity and, amazingly for such a remote location, wifi!

I spent three days at the cabin waiting for a storm to pass, eating, sleeping and enjoying simple conversations with my hosts. Ruslan was a true mountain man, he would spend ten months a year at the cabin where he supported himself with fish from the lake, game from the forest and bread from his own stove. Rifles hung on every wall of the cabin and traps were stacked in a corner waiting for winter when the region’s oldest profession, the fur trade, would begin again.

When I told the others of my bear encounter they warned me that further to the south, where I was heading, there were even more of the feared beasts. Ruslan told me that earlier in the year he had seen thirteen in a single day. I was worried about going on, not only about the bears but the fact that Ruslan’s cabin was the last human settlement for hundreds of miles. There were no towns anywhere else in the region, no camps, no roads, not even any proper trails, just the silence and solitude of the Taiga. I realized how vulnerable I was and how much I was at the mercy of the landscape. I had no satellite phone, no emergency beacon, no GPS, and no gun. If something went wrong no one would ever know. ‘In the Taiga’, as the locals say, ‘there are no witnesses’.

On the third morning the storm had passed. Ruslan restocked my supplies of rice, flour and sugar and I loaded Katchula ready to go. I knew if I stayed any longer I would lose my nerve and never leave the comfort and safety of the cabin. Ruslan told me that if I travelled south and then crossed the mountains to the east I would find the valley of the Khalkan River, here he told me, though I could tell he wasn’t completely sure, I would find camps of tipi dwelling Evenki reindeer herders. These mysterious tribes still lead a nomadic lifestyle with their reindeer supplying them with everything they need to survive in one of the harshest environments on the planet.

Handshakes from Ruslan and Alex and hugs from Sakhayana were my farewell. Riding off into the forest around the lake shore, I looked back to see my friends waving, they were the last people I would see for nearly three weeks.

The way ahead was even more rugged than that I had already passed through. Due to the permafrost, a meter or so below the ground, snowmelt and rainfall has little chance to drain away, and the result is a waterlogged landscape of bogs and swamps, inches thick layers of slippery mosses, fallen trees and thick scrub. Progress was slow and the terrain mostly too rough to ride on, so for days on end we picked our way through the shambles a few meters at a time.

A few days after leaving the cabin it started snowing heavily and didn’t let up for 48 hours. This added knee deep powder snow on top of the already soggy ground. So exhausting was the slog through this cold, wet nightmare that I was reduced to forcing myself to take 50 steps at a time counting each one, and then rest for 25 breaths before taking 50 more, but by this method we inched our way across Siberia.

The snowfall marked the end of the short Siberian summer and the beginning of the great cold that would soon blanket the land. Almost overnight the green needles on the larch trees turned to a stunning golden, beautiful to see but difficult to enjoy as the temperature dropped each day. Nights were painful; tormented by the cold, I would sleep in everything I had to wear with Dogor curled next to me and I’d still freeze. In the morning my boots, wet from the previous day, would be frozen solid, I would have to light a fire to thaw them out.

We finally made it into the valley of the Kalkhan River. Standing on top of a ridge, I scanned the vastness below desperately hoping to spot an Evenki camp, looking for the movement of a reindeer herd or rising smoke from cooking fires. But there was nothing. And even without visual confirmation, there was a strong sense of the absence of human life anywhere in the valley. I could just feel that there wasn’t a soul to be found, that apart from Dogor and Katchula, I was completely alone.

And yet the valley wasn’t empty. We twice more encountered bears, but thankfully these wanted nothing to do with our little caravan and fled into the forest leaving me with only a glimpse. I saw herds of wild reindeer, a young moose wandered past my camp one morning, I found wolf tracks in the snow, ducks and geese inhabited the many lakes we passed and turkeys and other game birds would burst from the undergrowth throughout the day. But there were no people, not even any sign that anyone had ever come this way, no tracks, no old camp sites, no garbage. Nothing.

Without finding the Evenki I was faced with another problem; I was almost out of food. My supply of rice and flour steadily dwindled and the chocolate bars I had brought in case of emergency were soon just a regular part of the menu. Often in the afternoon I would hit the wall, completely drained of energy, and I would find myself in a state of not even being able to take another step or climb onto Katchula’s back. The squashed and mangled bar of chocolate in the bottom of my bag was literally a life saver, giving me the strength to get through the rest of the day.

One evening we camped next to a small lake as the darkness of another freezing night fell. I made a fire and boiled water for tea with Dogor beside me waiting expectantly for his only meal of the day, half of my rice ration.

“I’m sorry boy, it’s all gone.” I told him. He kept sniffing my cup but finding nothing gave up and crawled into the tent. For the next four days we lived on throat lozenges raided from my medical kit and blue berries that grew in carpets on the hillsides. Dogor was so hungry that even he ate them, although at times he was able to catch small rodents which he would dig from the ground and swallow whole with a crunch.

Finally, one beautiful morning, we crossed the hills above Lybunkur Lake and the red tin roof of Ruslan’s cabin came into view. An hour later Dogor was wolfing a bowl of fatty reindeer meat and I was doing the same to a plate of pasta. We’d made it back to safety, warmth, good food and friendly company. After resting a few days, I said goodbye to Ruslan once more and we rode back to Tomtor to complete a journey of five weeks and 450 kilometers.

Saying goodbye to Katchula and Dogor was heartbreaking. They had both become friends, bravely enduring the hardships and never letting me down, and together we had made it through the toughest time of my life. Saying farewell to the Taiga was easier; I had found a beautiful but cruel environment, unspoilt but unforgiving, stunning in its vastness, silent and majestic but uncaring of those that wandered into it. The Taiga is nature at its rawest and indifferent, anything living that enters it or is born there, man or beast, is subject to the same laws and rules, whether one survives or not is not the Taiga’s concern.