高野山:雲の中の寺

On a massive elevated superhighway, we scream past the city of Osaka at a height that gives the sensation of low altitude flying. The grey skies mirror the concrete sprawl below. We’d hoped for a sunny day to visit the mountain temples of Koya-san in Japan’s Wakayama Prefecture but it wasn’t to be. Our distance above the city hides the intricate details of Osaka, a place where, if you know where to look, you can find everything.

The occasional urban rice paddy lies between the housing blocks like a piece of the past someone forgot to clean up. Rivers very slowly flow between neat concrete river banks lest they step out of line and try to overflow. With the mass of humanity that is Japan, everything must be kept in order.

After paying tolls at an off-ramp, we exchange the highway for tiny lanes through residential areas until we find the right turnoff to Koya-san. The streets are narrow, so narrow in fact that as our car passes, I must only be a couple of metres from the people inside having lunch or watching TV. I can’t see anyone. Japan was once an insular nation and although it may have opened to the world, the Japanese live much of their lives behind closed doors. The shutters are always shut, the curtains are always drawn.

Soon the houses get larger, the roads smaller and the rice and vege fields more common -the spotless, gleaming fast food joints and convenience stores less frequent. Compared to the city behind us, the mountains rising ahead are dark and empty. Suddenly we are in forests of very old cedar and big bamboo with real streams free to take their own course. Once upon a time companies of Ninja hid and trained here.

The narrow, winding road to mountaintop Koya-san is busy but everyone’s coming down at the end of a public holiday. By the time we arrive in the late afternoon, the place is nearly empty. The Daimon gate guards the entrance to Koya-san township, a village with only one main street. The massive gate has been rebuilt several times, and the present edifice was completed in 1705. Hokyo Uncho, guardian deities on either side, protect the area beyond. In the tiny smoky tourist office next to it we pay for our accommodation for the night. Most visitors to Koya-san stay in one of the 53 temples which offer shukubo, traditional lodgings for pilgrims or travellers.

Koya-san is described as an ‘alpine basin’, a thousand metres above sea level and surrounded by eight holy peaks. Like the petals of a lotus flower, the village and temples are in the centre, and it is one of Japan’s most sacred places.

The Buddhist master Kukai (known as Kobo Daishi after his death) founded the Shingon school of Buddhism here after travelling to China in 803 to receive the teachings from masters in present day Xian. Shingon is more closely related to Tibetan Buddhism than to the better known, ego-snapping Zen most often associated with Japan. Under the exceptional guidance and influence of Kukai, the region flourished, and at one time there were 1500 monasteries, but today there are still an impressive 117. Over the centuries the peace of the mountains has been frequently broken by the usual overthrows and upheavals; however, Koya-san is still a very active centre for Buddhist study and is far from being just a tourist attraction, something that could be said of the more famous, urban based temples of Kyoto.

Up a steep driveway we arrive at our lodgings for the night, the temple of Fudo-in, consecrated in 1150. Getting out of the car, two young monks trimming a hedge with an electric prunner stop what they’re doing and address us with deep bows and polite greetings. The obo-san or head monk, a young man in grey robes, comes to show us to our traditional tatami room (room covered with rush mats) with sliding paper screens, low tables, scrolls of elegant calligraphy and a flat screen TV. After we are settled in, the monk tells us we can nominate anyone we wish him to pray for, for a fee which is adjusted according to the frequency and length of the prayers.

Given the fact that I’m staying in a religious institution, I ask the monk if there are any rules guests are expected to follow?

“Rules?” he looks somewhat puzzled by the question, “No, there are no rules here.”

As he stands to leave, he remembers to tell us that dinner will be served at six o’clock, “And would you like beer or Japanese sake with your meal?”

We are then left in peace to sip green tea. The sliding screen closes, his footfalls shuffle away. I look at my friend, something is very odd around us; “What’s that sound?” It is the sound of one hand clapping! Silence! A rarity in Japan, Koya-san must be the quietest place in the country and without realizing it from now on we tend to speak in whispers.

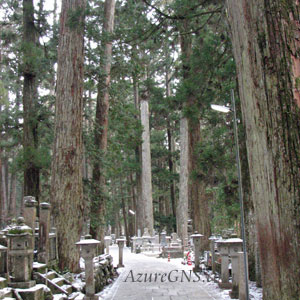

The temple of Okuno-in is Koya-san’s main site. It is reached by a long stone path through a forest of massive cedars hundreds of years old. The walk is actually through a cemetery containing the ashes and bone fragments of hundreds of thousands placed there over a thousand years. Covered in moss among the trees and lost in the undergrowth are acres of stone lantern-shaped monuments and granite memorials like giant chess pieces. Tiny and not so tiny stone Buddhas line the route, some so ancient the trees have begun to grow around them.

Small groups of Shingon pilgrims pass in white robes and round cone shaped straw hats. They are at the end of the 24 kilometre Choishimichi path described by the tourist brochure as ‘the journey and climbing of this path is a true test of faith and a gesture of worship’. On the path, they have counted 180 stone markers set 109 metres apart, and the walkers look tired but content.

Monuments in memory of different groups of the dead are found amidst the general deceased. From one dedicated to aborted babies to another that commemorates the lives lost in World War Two in Borneo; Japanese, local Borneans and Australian troops. Compassion is limited only to the number and variety of sentient beings, and is therefore limitless.

My earlier disappointment at the dismal weather turns out to be a perfect Koya-san day and far more atmospheric than if it had been sunny. Quiet and stillness pervade the trees, mist drifts around the graves and peaks beyond are thick in clouds. The rest of Japan below is blissfully cut off and the frantic city I woke up in that morning has no reality here. I feel disorientated and quite unsure of where I actually am with no static points to give myself a reference. All I can perceive is the place and time I am standing in right now, everything else seems momentarily irrelevant.

The pathway reaches the Toro-do, the Lantern Hall, lit with hundreds of lamps, two of which are said to have been burning continuously for nine hundred years. Behind the Toro-do is Kobo Daishi’s tomb, a small wooden structure covered in moss and reverently set away from the limits visitors can go. No one speaks in more than a hush, and photos are not allowed for the Great Master inside is said to be not dead at all but merely seated in a state of deep perpetual meditation for the last 1172 years. He waits for the coming of Matreiya, the future Buddha. So seriously is this belief held that breakfast and lunch has been offered in front of the tomb daily since his entrance.

Returning along the cemetery path, night is already falling. Japanese avoid the place during the dark hours. They may have created the most modern nation on Earth but old superstitions run deep and with the number of graves, this place must surely be haunted. Mist thickens with the quiet, only crows call in the treetops and somewhere unseen a deep gong tolls.

Early in the evening the monk takes us to another private tatami room where dinner awaits us. Over the centuries the temples of Koya-san developed a unique style of food preparation known as ‘shojun-ryori’. No meat of any kind, no animal products and no garlic or onion; these vegetables are said to hinder the development of meditative states. Trays are laid out with a dozen tiny dishes, none appear to be more than a mouthful but collectively they make a satisfying and non-excessive dinner, subtle and delicate tastes of sesame tofu and tiny wild mushrooms. And despite the auspicious surroundings there is a vending machine stocked with cans of beer in the hall.

Back in the room futons have been mysteriously unrolled and bedding prepared. The TV remains silent. Evenings are early here and mornings are even earlier. At 6am I am following the monk again to Fudo-in’s main temple for morning prayers. While not mandatory, attendance is a rare opportunity to experience the daily workings of a Japanese temple. Inside the dark ninth century temple I kneel on bare tatami. Buddhas shine from within the darkness surrounded by dozens of ritual symbols and objects. The monks chant rhythmic prayers and strike deep metal bowls, sounds that linger long after the syllables are completed. I burn incense and make prayers before returning to my knees. Western joints are not accustomed to such postures for long but the pain and resisting the desire to move are all part of the lesson.

Breakfast is laid out in our room when we return, intricate dishes of I’m not sure what prepared by the obo-san’s wife.

“I studied for two years,” the monk tells me “to get my license and then took over Fudo-in from my father, this temple has been in my family for…” he tries to work out the dates from the Meiji Era when Japan first began to open to the outside, “… a long time!”

I ask him about being married as in most other Buddhist states marriage or any kind of sexual contact is off limits for the ordained.

“Monks like me are lucky these days, and for a long time, we weren’t allowed to have a wife. At Koya-san, until 1872, women were forbidden from even coming here.”

On the drive back to Osaka, we take the back way around the mountain. Just beyond the town, we are the only vehicle on the road for the next few hours, something I wouldn’t have thought possible in Japan where the car is king. Somehow, we get lost and climb back into the hills of dense cedar forest, and soon the road is almost too narrow even for our tiny vehicle. Tree trunks crowd to the road’s edge with barely enough room to squeeze through, the canopies block out the sky, and it’s more like driving through a tunnel.

Oddly the landscape reminds me of Tibet, a land mostly devoid of greenery. In the darkness and quiet there is a primeval air, surprising in ultra-modern Japan. Perhaps it is the presence of holy Buddhist sites? Or perhaps it’s the fact that, like Tibet, Japanese culture was founded on shamanism? Trees, earth and water have a spirit and life force of their own and away from the panic-pace of the cities, the imps and elves still rule. Again, Japan has opened itself to the outside world but what is really Japan lies hidden somewhere, some would say this is the same as the Japanese psyche.

An hour later we are back on the superhighway and heading into Osaka under a hazy orange sun as the city settles down and starts up for the night. The temples of Koya-san I left that morning seemed impossibly distant, the darkness of the forests unreal, and in Okuno-in, Kobo Daishi meditates.