モンゴルのナーダム、競馬の最大の祭典

The biggest day on the Mongolian calendar is the midsummer festival of Naadam! Well, it’s actually the biggest three days on the calendar as the festival is usually held over a long weekend, and in fact most Mongolian’s take a long break over the summer anyway, some up to three months if they can!

Naadam has been held since the time of the great Mongolian emperor Chinggis Khan and his ceremonial banner of nine white yak tails is still flown at the festival today in his honor. Naadam consists of the ‘Three Manly Sports’ of horse racing, wrestling and archery. In the past these sports were, as the name suggests, only practiced by men, though these days women competitors have been admitted to horse racing and archery, while wrestling still remains the sole domain of men.

In the festival’s beginnings the three sports were part of the training to prepare men for war as the Great Khans expanded their empire with the help of the sword to stretch from the Pacific Ocean to Europe. These days Mongolians have put away their swords, but the festival is still seen as a great occasion and serious pride is at stake for those taking part. Wrestling champions often go on to fame and wealth as sumo wrestlers in Japan and being the owner of a winning Naadam horse brings enormous respect and honor to a nomadic family.

Naadam festivals are held across Mongolia at varying dates throughout the summer with the largest being staged in the National Stadium in the capital city of Ulaan Baatar. This version of the festivities is filled with color and ceremony, crammed with tourists and tickets sell out for high prices months in advance. Recently many locals consider the Ulaan Baatar Naadam to be commercialized and touristy and recommend visitors attend a local Naadam at a village far out on the steppe where the real spirit of Naadam can still be found.

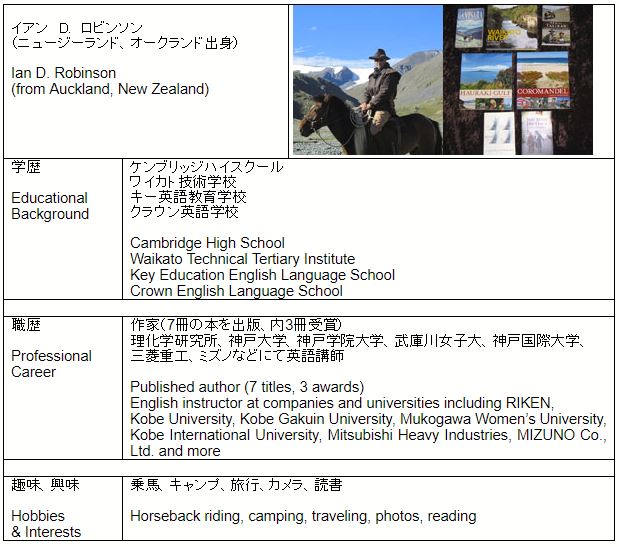

And so, I found myself in the village of Altay in Mongolia’s far west, about as far from Ulaan Baatar as you can get in Mongolia, in the heart of the Altai Mountains.

“So, where is the Naadam?” I asked my guide.

“It’s over there.” And she pointed to a single mud brick hut on a hillside in the middle of a vast sweeping valley. There wasn’t a single person there, it seemed we were the first to arrive.

“So, what time does it start?”

“At ten o’clock.” She told me. I looked at my watch, it was already ten-thirty. “Ten o’clock ‘Mongolian time’”, she added, guessing what I was thinking, “so when the people get here it will start.” And not long after people began to arrive, in jeeps, on motorbikes or on horses.

Soon the empty hillside was bustling with people, young and old. I watched as women hugged and men shook hands, exchanged snuff bottles or cigarettes. Many of those attending the festival were obviously related or old friends, and they may not have seen each other for months as nomadic camps could be several days journey apart. The Naadam was much more than a sporting event, it was a time for the people of the steppe to reunite with each other, share news about who had passed away and who had had a baby since the last time they’d met. It was also a time for gossip and flirting, nearby a group of teenage boys giggled and cast shy glances at a group of equally giggly but less shy teenage girls. In the few years these awkward moments could result in a wedding.

Wrestling matches were soon underway. Mongolian warriors in great leather boots with upturned toes but otherwise skimpily dressed in tiny blue or red outfits tussled in battles to throw each other to the ground. The winner of each bout raised his arms as an eagle’s wings and flew over the man he’d defeated in triumph.

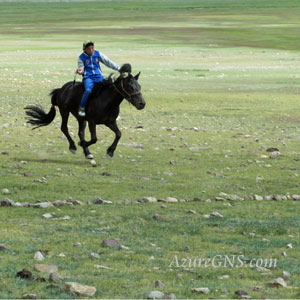

But the main event of the day was the horse racing, and everyone kept an eye on the horizon, watching for the cloud of dust that would mark the approach of the horses. The start of the race was an incredible twenty kilometers away with most Naadam races ranging from fifteen to thirty kilometers, and the horses are ridden without saddles. Even more incredible are the jockeys; only children are used from ages six to thirteen years old!

“This,” as I was later told, “is not only because they are smaller and weigh less so the horses can run faster, but also because children have less fear than adults so they’ll try and go faster.”

Suddenly a shout went up and people began to run down the hillside towards the finish line. The horses were coming! As the crowd pushed forward officials shouted at people to stand back and keep out of the way of the thundering but exhausted animals.

Soon the tiny figures in the distance grew and became clearer. Next to me a man shouted and threw his arm around the shoulders of another, his friend’s horse was in the lead on the home stretch to the finish.

As the sleek black horse crossed the line the spectators rushed to the sweat soaked steed; to touch the winning horse is considered good luck and as the boy jockey slid from the horses’ back it was slapped by dozens of hands. The horse was led around and around in circles to help it calm down after galloping for half an hour and was then scraped with a type of wooden spatula to remove the sweat preventing it from cooling too quickly and catching a cold.

I watched as other riders crossed the line. As each horse finished its race, a father or older brother would come forward and taking the reins from the jockey, lead the horse away to cool down and rest. The young boys who had just galloped across the steppe were exhausted; they virtually fell from their horses, and some were so tired and in such pain from the rigors of the ride they could barely stand up. And yet they were ignored by their parents; none of the fathers hugged their sons or gave them a high five, no one said anything like ‘well done’, ‘good race’ or ‘you did your best’; the boys were left to stagger away to find a water bottle. It seems that Naadam is a day only for the horses to shine and be stars!